A la recherche du meilleur casino en ligne pour 2024? En tant qu’expert de premier plan dans le domaine des jeux d’argent, j’ai personnellement pris le temps de tester 98 casinos en ligne et d’évaluer chaque opérateur ainsi que leurs fonctionnalités à l’aide d’une méthodologie bien rodée.

Joueur depuis de nombreuses années, ayant testé la plupart des meilleurs casinos en ligne français, j’ai pu acquérir beaucoup de connaissances et j’ai appliqué des critères stricts pour évaluer la sécurité de l’utilisateur, le service client, ou encore l’offre de jeu pour chaque casino présenté dans ce top 10.

Meilleur casino en ligne: les points à retenir

- Les conditions de mise seront toujours accessibles, permettant un retrait rapide de vos gains.

- Les meilleurs casinos en ligne seront toujours détenteurs d’une licence délivrée par une autorité des jeux crédible et reconnue.

- Les ludothèques proposées doivent être conséquentes et encadrées par des fournisseurs de renom

- Les bonus doivent être variés, que ce soit pour l’offre de bienvenue ou pour récompenser les joueurs fidèles et actifs.

Casino en ligne fiable: Notre sélection pour France 2024

Avant de commencer mes évaluations, voici la liste des 10 meilleurs casinos en ligne que nous présenterons dans cet article. Voici une description rapide des points forts notables de chaque plateforme :

- Lucky Treasure : Casino en ligne gratuit avec un bonus de bienvenue alléchant et presque imbattable, offrant 150 % jusqu’à 1200 €. C’est un point important qui vous permettra de disposer d’une bankroll plus importante d’entrée de jeu.

- King’s Chance : Un mode d’entraînement très apprécié est disponible afin de pouvoir tester l’ensemble des jeux gratuitement. Les débutants pourront ainsi tester le site sans investir d’argent.

- Happy Hugo : La plateforme est l’une des seules à proposer des bonus et promotions sans conditions de mise. Rares sont les casinos qui n’imposent pas de wager. Vos gains peuvent donc être retirés quasiment instantanément.

- Lucky8 : L’interface performante et moderne de Lucky8 promet une expérience visuelle réussie. L’ergonomie est au rendez-vous grâce à un système de filtre, vous permettant de retrouver vos jeux favoris en quelques clics.

- Play Regal : En plus du bonus de bienvenue, des promotions alléchantes sont mises en place tout au long de la semaine. Les joueurs peuvent être récompensés par des spins gratuits, ou encore de l’argent cash.

- Spinanga : Un cashback de 25 % jusqu’à 200 € est valable sur les jeux de casino live de la plateforme. Aussi, les joueurs VIP pourront profiter d’un cashback hebdomadaire de 15 % jusqu’à 3 000 €.

- Gxmble : L’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne en ce qui concerne la sécurité et la fiabilité. Gxmble assure une véritable protection à ses joueurs, grâce à de nombreux systèmes et logiciels vous assurant une expérience client irréprochable.

- Seven Casino : Déblocable sur vos quatre premiers dépôts, le bonus de bienvenue propose un boost total de 450 % jusqu’à 7 500 €. Ce type de bonus avantagera clairement les joueurs expérimentés voulant miser des sommes importantes.

- Leon : Casino en ligne gratuit avec une ludothèque très complète de plus de 3000 machines à sous. De plus, la section paris sportifs propose des cotes compétitives pour parier sur toutes les grandes compétitions sportives.

- Ruby Vegas : La plateforme propose une riche collection de jeux de casino en direct. Accessible aussi par l’intermédiaire d’un smartphone ou d’une tablette, le croupier en direct vous donnera l’impression d’être dans un casino physique.

Meilleur casino en ligne France : Mon top 10 en détail

1. Lucky Treasure : Casino en ligne gratuit avec un des meilleurs bonus casino en ligne

Fraîchement arrivé sur le marché en 2023, Lucky Treasure est notre top 1 des meilleurs casinos en ligne, exploité par la société Gleneagles B.V. Nous allons analyser soigneusement l’ensemble des conditions d’utilisation que propose le site :

📃 Licence et sécurité

La sécurité sur la plateforme est optimale grâce à la présence d’un cryptage SSL de haut niveau, garantissant une protection totale de vos données personnelles et financières. Lucky Treasure est détenteur d’une licence de Curaçao qui est reconnue dans le secteur des jeux d’argent.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Le catalogue est très complet et met à disposition plus de 3000 titres comprenant des machines à sous, des jackpots progressifs, des jeux de table, ou encore le poker vidéo et le casino en direct. Des émissions télévisées animées par de véritables présentateurs sont également disponibles, et sauront vous mettre dans l’ambiance.

💻 Logiciels

Sur Lucky Treasure, vous pourrez retrouver des fournisseurs qui ont déjà largement fait leurs preuves. Parmi eux, on distingue Betsoft, Booongo, Play Son, Pragmatic Play, Fugaso, Arcadem, ou encore Red Drake et Spribe.

💰 Bonus

Chez Lucky Treasure, on vous propose un bonus de bienvenue de 400 % jusqu’à 1200 €. L’opérateur récompense par ailleurs ses joueurs via des promotions régulières tout au long de la semaine, dont un cashback pouvant aller jusqu’à 15 % de vos pertes.

📱 Application mobile

Malheureusement, le casino français en ligne Lucky Treasure ne dispose pas encore d’une application dédiée aux appareils mobiles. Malgré tout, il est possible de se connecter de manière très simple via votre navigateur. Vous profiterez d’une version mobile très bien adaptée aux petits écrans, tout en conservant une fluidité similaire à la version PC.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Beaucoup de méthodes de paiement sont disponibles sur le site, et toutes sont fiables et sécurisées. Parmi les différentes options, vous aurez le choix entre :

- Les cryptomonnaies (BTC, LTC)

- Les portefeuilles électroniques

- Les cartes bancaires

- Les virements bancaires

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Sur le site Lucky Treasure, vous devrez déposer un minimum de 20 €, que ce soit via une carte bancaire, un virement bancaire ou des cryptomonnaies. Pour les retraits, le minimum accepté par le casino est de 30 €, sauf pour le virement bancaire qui nécessite un retrait minimum de 100 €. À noter qu’un délai de 24h à 48h est requis pour pouvoir récupérer vos gains.

📞 Service client

Le support de Lucky Treasure est effectivement à la hauteur des meilleurs casinos en ligne, et j’ai apprécié le fait que les conseillers soient réactifs et compétents, en plus d’être francophones. L’équipe est disponible 24h/24 et 7j/7 via un chat en direct, mais aussi par l’intermédiaire d’une ligne téléphonique et d’une adresse mail.

👍 Avantages

- Bonus de bienvenue avantageux

- Version mobile fluide et stable

- Service client facilement joignable

- Belle offre de jeux de casino

- Casino fiable et sécurisé

👎 Inconvénient

- Pas d’application mobile

2. King’s Chance : meilleur casino en ligne France pour son mode d’entrainement gratuit

Après un test parfaitement concluant, j’ai décidé de vous présenter le casino en ligne King’s Chance. La plateforme vous plonge dans un univers de luxe via une interface très bien conçue et adaptée à tous types de joueurs.

📃 Licence et sécurité

King’s Chance possède plusieurs certificats de cryptage à jour afin de protéger au mieux vos données personnelles sur les serveurs. Pour crédibiliser sa présence sur le marché, King’s Chance a obtenu une licence de jeu de Curaçao, et travaille uniquement avec des fournisseurs de jeux également sous licence.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Selon moi, la collection de jeux proposée par le meilleur casino en ligne est largement satisfaisante pour la majorité des joueurs. Avec des milliers de jeux, la plateforme intègre plusieurs catégories comme les machines à sous, les jeux de table, les mini-jeux, ou encore le casino live.

💻 Logiciels

L’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne de France s’est associé avec une vingtaine de logiciels de casino, dont certains sont les meilleurs du secteur. Depuis le lobby, vous pourrez naviguer à travers les créations de Playson, Fugaso, Betsoft, Booming Games, ou encore Spribe.

💰 Bonus

Le bonus de bienvenue sur King’s Chance est très avantageux et offre aux joueurs un boost jusqu’à 10.000 € sur vos premiers dépôts. Voici la répartition du bonus :

- Premier dépôt : 100 % de bonus jusqu’à 2500 € + 30 spins gratuits

- Deuxième dépôt : 100 % de bonus jusqu’à 2500 € + 30 spins gratuits

- Troisième dépôt : 100 % de bonus jusqu’à 2500 € + 30 spins gratuits

- Quatrième dépôt : 50 % de bonus jusqu’à 1250 € + 15 spins gratuits

- Cinquième dépôt : 50 % de bonus jusqu’à 1250 € + 15 spins gratuits

À noter que le wager est de 50x sur ce site, ce qui est un peu élevé.

📱 Application mobile

Grâce à la technologie HTML5, King’s Chance a lancé une version mobile sans aucun téléchargement, accessible depuis Safari, Chrome, ou n’importe quel autre navigateur web mobile. Après avoir testé la version mobile sur iOS et Android, je peux maintenant dire que la plateforme est parfaitement adaptée aux petits écrans, et ne souffre d’aucun bug ou ralentissement.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Effectuer un dépôt sur King’s Chance est vraiment très simple grâce à la multitude de méthodes de paiement mises en place. Les joueurs pourront déposer par l’intermédiaire d’une carte bancaire, d’un virement bancaire, d’un ticket prépayé, ou encore via un portefeuille électronique. En dehors du virement bancaire, toutes les transactions sont instantanées et n’engendrent aucun frais.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Pour les dépôts, un minimum de 30 € vous sera demandé pour l’ensemble des moyens de paiement. Cependant, il est possible de déposer encore moins via Cashlib (5 €), ou eZeewallet (20 €), ce qui peut être une bonne alternative pour les débutants. Du côté des retraits, vous pourrez retirer entre 100 € et 2500 € par semaine après avoir confirmé votre identité.

📞 Service client

Il est important de se sentir épaulé sur un site de casino en ligne. Pour cela, l’équipe de King’s Chance est disponible par mail ou encore via un chat en direct. Le support se montre vraiment très professionnel et à l’écoute.

👍 Avantages

- Bonus de bienvenue généreux

- Méthodes de paiement diversifiés

- Service client compétent

- Navigation intuitive

👎 Inconvénients

- Conditions de mise élevées (50x)

- Absence de promotions hebdomadaires

3. Happy Hugo : meilleur site de casino en ligne pour ses conditions de mise inexistantes

Découvrons ensemble le casino Happy Hugo, qui propose des bonus et promotions sans conditions de mise, ce qui est assez rare pour être signalé. Voici les différents points à retenir pour ce nouveau casino en ligne :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Happy Hugo est particulièrement attaché à la sécurité de ses utilisateurs sur le site, et c’est pour cela qu’il dispose de plusieurs logiciels, dont un générateur de nombres aléatoires, afin d’assurer l’intégrité de l’ensemble des jeux de la plateforme. Vos informations bancaires et personnelles sont également bien protégées grâce à un cryptage SSL de haut niveau. De plus, le site détient une licence de Curaçao, comme beaucoup d’autres casinos de renom.

🎲 Jeux de casino

L’offre de jeux de casino est vraiment conséquente sur Happy Hugo avec pas moins de 4500 titres répertoriés, comprenant des machines à sous, du blackjack, de la roulette, ou encore du casino live animé par de véritables croupiers.

💻 Logiciels

Le catalogue de jeux de Happy Hugo est fourni grâce à sa collaboration avec de nombreux fournisseurs, offrant une grande diversité dans le choix des jeux. Parmi les développeurs présents sur la plateforme, on retrouve certains poids lourds de l’industrie comme Evolution, Pragmatic Play, Hacksaw, Nolimit City, ou encore Play’n GO.

💰 Bonus

Pour les nouveaux venus, Happy Hugo offre un package lors de vos trois premiers dépôts, et il vous sera possible de recevoir jusqu’à 1000 € + 150 spins gratuits. Du côté des promotions, l’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne propose des cash drops quotidiens, des tournois hebdomadaires, ou encore des bonus de dépôt tout au long de la semaine.

📱 Application mobile

Aucune application mobile n’est encore proposée, cependant, il est possible de se connecter directement au logiciel via le navigateur de votre appareil mobile. Que ce soit sur iOS ou Android, l’interface est composée des mêmes fonctionnalités que sur ordinateur, tout en proposant une expérience fluide et dynamique.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Pour déposer de l’argent sur le site, Happy Hugo met à disposition des moyens de paiement comme le virement bancaire, la carte bancaire, Trustly, Sofort, Neteller, Skrill, ou encore Siru mobile.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Selon la méthode choisie, le dépôt minimum demandé pourra varier, mais globalement, un montant de 20 € minimum sera exigé. Pour pouvoir réaliser un virement bancaire, un dépôt de 100 € est imposé. Pour les retraits, vous pourrez retirer vos gains gratuitement deux fois dans le mois sans que le casino vous impose un minimum à respecter.

📞 Service client

En plus de mettre une FAQ à disposition des utilisateurs, un chat en direct est accessible facilement sur chaque page du site pour pouvoir interagir avec un conseiller en temps réel. Une adresse mail est aussi disponible pour pouvoir joindre un agent francophone. Le délai de réponse est rapide et des solutions vous seront très vite apportées.

👍 Avantages

- Un catalogue de jeux très vaste

- Un bonus de bienvenue jusqu’à 10.000 €

- Une version mobile ergonomique et fluide

👎 Inconvénients

- Peu d’informations sur le programme VIP

- Peu de méthodes de paiement

4. Lucky8 : meilleur casino gratuit en ligne pour son interface et sa fluidité

L’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne au monde, Lucky8, assure des services et des fonctionnalités bien au-dessus de ses concurrents. Regardons de plus près ce que propose la plateforme :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Lucky8 dispose d’une licence remise par la Curaçao eGaming, et a beaucoup investi pour permettre une sécurisation optimale des données personnelles et financières des joueurs. Grâce à un cryptage SSL de haut niveau et à un logiciel générateur de nombres aléatoires, la plateforme coche toutes les cases d’un site fiable et sécurisé à 100 %.

🎲 Jeux de casino

L’opérateur intègre un catalogue de jeux bien étoffé, dont des centaines de machines à sous différentes, des jeux de casino en direct, ainsi que des jeux de table comprenant des tables VIP. Dans la section casino live, des jeux télévisés animés par de véritables présentateurs sont aussi disponibles.

💻 Logiciels

Avec un catalogue de plus de 2100 jeux différents, je me doutais bien que l’établissement était en collaboration avec certains des meilleurs fournisseurs du marché. Parmi eux, on retrouve Yggdrasil, Play’n GO, Pragmatic Play, Evolution Gaming, Quickspin, Rexal Gaming, ou encore Red Tiger.

💰 Bonus

Le casino en ligne Lucky8 propose un bonus très avantageux de 200 % sur votre premier dépôt jusqu’à 500 € + 600 spins gratuits. Régulièrement, Lucky8 organise une opération qui a pour but de récompenser les joueurs les plus actifs via des spins gratuits et de l’argent en cash.

📱 Application Mobile

Le casino gratuit en ligne Lucky8 n’a pas encore mis en place d’application, mais il vous sera tout de même possible de vous connecter à la plateforme via le navigateur de vos appareils mobiles. Grâce à la technologie HTML5, les smartphones et tablettes Android et iOS sont compatibles, et fonctionnement très bien avec l’interface du site.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Lors de votre premier dépôt, vous pourrez découvrir une multitude de moyens de paiement. Vous pourrez choisir de régler en carte bancaire (Visa, Mastercard), via un portefeuille électronique (Skrill, Neteller), ou encore avec une carte prépayée (Paysafecard) et en virement bancaire. Dommage qu’il ne soit pas encore possible de procéder à un paiement en cryptomonnaies.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Sur Lucky8, le minimum de dépôt est de 10 €, ce que je trouve tout à fait convenable par rapport à d’autres casinos en ligne. Vous avez le choix entre des sommes prédéfinies ou alors de rentrer vous-même le montant souhaité. Par la suite, pour retirer vos gains, la plateforme autorise un retrait à partir de 30 € jusqu’à 2500 € par semaine.

📞 Service client

Le service client de Lucky8 est tout à fait à la hauteur et vous apporte un support 24h/24 et 7j/7. Les conseillers francophones sont joignables très facilement via un chat en direct, ainsi que par l’intermédiaire d’une adresse mail. Une FAQ est également disponible afin de répondre aux questions récurrentes.

👍 Avantages

- Meilleur casino live en ligne

- Ludothèque conséquente et variée

- Grand choix de méthodes de paiement

- Bonus de bienvenue alléchant

👎 Inconvénients

- Wager un peu élevé (40x)

- Pas de paiement possible via des cryptomonnaies

5. Play Regal : meilleur casino live en ligne du moment

Récemment arrivé dans le milieu des casinos en ligne, Play Regal est exploité par la société Logic Online Corp B.V. Passons en revue les différentes caractéristiques du site :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Play Regal dispose d’une licence délivrée par l’autorité des jeux du Curaçao, faisant de la plateforme une valeur sûre. Avec un protocole de cryptage de 256 bits, toutes vos transactions sont sécurisées, vous assurant une protection maximale contre tous types de piratages ou intrusions. Conformément à la RGPD, vos données personnelles et financières sont collectées, stockées, et enfin supprimées.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Avec une ludothèque de plus de 2000 jeux de casino, Play Regal est l’une des seules plateformes en ligne à proposer un taux de retour aussi élevé aux joueurs (entre 95 et 97 %) sur l’ensemble de ses machines. Au menu, vous retrouverez des machines à sous, des jeux de table, des mini-jeux, mais aussi une section casino live.

💻 Logiciels

Assisté par des grands fournisseurs de jeux de casino comme Pragmatic Play, Yggdrasil, BetSoft et Booming Games, Le casino Play Regal est en capacité d’offrir la meilleure des expériences client qu’il est possible de trouver parmi toutes les offres du marché.

💰 Bonus

Le wager accessible de 30x vous donnera la possibilité de retirer vos gains assez vite, tout en profitant d’un bonus de bienvenue global de 3 000 € + 100 spins gratuits. À noter que ce dernier se débloque entièrement via vos trois premiers dépôts. Côté promotions, Play Regal met régulièrement en avant des opérations comme la roue de la fortune, les bonus de dépôt rapide, ou encore du cashback pour les joueurs les plus investis.

📱 Application mobile

Contrairement à la plupart de ses concurrents, Play Regal à su mettre au point une application dédiée qui peut être téléchargée directement sur le site de l’opérateur. L’application est compatible avec Android et iOS et propose une bonne ergonomie ainsi qu’une belle stabilité. Toutes les fonctionnalités présentes sur ordinateur sont également disponibles sur l’application, tout comme le catalogue de jeux de casino en ligne.

💳 Méthode de paiement

Pour s’adapter à la plupart de ses utilisateurs, l’opérateur propose un choix assez large de moyens de paiement dont les cartes bancaires, les cartes prépayées, les portefeuilles électroniques, mais aussi les cryptomonnaies (BTC, LTC, ETH).

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Pour toutes les méthodes de paiement proposées, Play Regal demande un minimum de dépôt de 15 € qui vous seront crédités instantanément sur votre compte casino. En ce qui concerne les retraits, le site vous autorise à retirer de 100 € à 1500 € par semaine, ce qui est une fourchette raisonnable par rapport à la concurrence. Attention, les retraits se font uniquement via virements bancaires, Skrill, ou par cryptomonnaies.

📞 Service client

J’ai personnellement analysé de très près le service client en tentant de contacter un conseiller. Finalement, j’ai obtenu une réponse rapide d’un agent francophone qui a su me renseigner et répondre à mes interrogations. Il est possible de contacter le support par e-mail, mais aussi par téléphone et live chat.

👍 Avantages

- Condition de mise accessible (30x)

- Catalogue bien étoffé de plus de 2000 jeux

- Bonus de bienvenue très attrayant

- Dépôt minimum de 15 €

👎 Inconvénient

- 300 € de retrait minimum pour un virement bancaire

6. Spinanga : meilleur bonus casino en ligne et cashback du marché

On peut dire que ce casino bookmaker a mis les petits plats dans les grands avec une ludothèque bien fournie et une multitude de bonus avantageux pour les joueurs actifs. Analysons les caractéristiques de la plateforme :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Cet opérateur détient une licence délivrée par les autorités du Curaçao et met en place toutes les mesures nécessaires pour sécuriser vos transactions, ainsi que vos données personnelles. Cryptage SSL, logiciel générateur de nombres aléatoires, tout est présent pour vous garantir une fiabilité optimale.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Via le lobby, vous aurez la possibilité de retrouver toutes les sections de jeux différentes comme les machines à sous, les jeux de table, le casino en direct avec croupiers, ou encore les paris sportifs proposant aux joueurs de pouvoir miser sur des matchs de tennis, de basketball et de hockey. Au total, Spinanga recense plus de 4000 jeux dont plus de 1650 machines à sous.

💻 Logiciels

Le catalogue de jeux est essentiellement fourni par les meilleurs éditeurs du marché dont NetEnt, Pragmatic Play, Evolution Gaming et BetSoft. Pragmatic Play produit notamment la majorité des 150 titres de jeux de casino live présents sur la plateforme.

💰 Bonus

Le bonus de bienvenue est un des atouts de Spinanga Casino et vous offre un bonus de 100 % jusqu’à 500 € sur votre premier dépôt. En plus de ça, vous pourrez profiter de 200 spins gratuits et d’un bonus crab. L’offre de cashback est également très généreuse et vous propose de récupérer 25 % de vos pertes jusqu’à 200 €. Pour les joueurs VIP, il sera possible de débloquer un cashback de 15 % jusqu’à 3 000 €.

📱 Application mobile

Le site Spinanga est conçu en HTML5 et est compatible avec iOS et Android. Depuis le navigateur de votre appareil mobile, vous pouvez accéder à la plateforme sans avoir à télécharger quoi que ce soit. Une bonne connexion internet est requise pour pouvoir jouer dans de bonnes conditions et éviter les ralentissements lors d’une partie.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Afin de convenir à un grand nombre d’utilisateurs, le casino Spinanga vous permet de réaliser votre premier dépôt via une multitude de méthodes de paiement, dont les cryptomonnaies. Les cartes bancaires, les virements bancaires, les cartes prépayées, ou encore les portefeuilles électroniques et cryptomonnaies seront à votre disposition au moment du règlement.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Le casino Spinanga n’est pas trop regardant sur le montant minimum à déposer sur le site. En effet, vous pourrez commencer à jouer en déposant un minimum de 10 € avec la plupart des moyens de paiement proposés. Pour les retraits, il vous sera possible de retirer un minimum de 10 €, tandis que le maximum est fixé entre 2500 € et 5000 € selon la méthode choisie.

📞 Service client

En cas de difficulté, vous pourrez contacter l’assistance via un chat en direct ou une adresse mail. L’équipe de Spinanga est très qualifiée, et formée pour répondre à toutes les requêtes des joueurs. Le délai de réponse est instantané via le chat, tandis que par mail, un délai d’environ 24h pourra être observé.

👍 Avantages

- Une offre de cashback très généreuse

- Un catalogue de jeux très diversifié

- Plus de 1650 machines à sous

- Un dépôt minimum de 10 €

👎 Inconvénients

- Pas de bonus sans dépôt

- Pas d’application mobile

7. Gxmble : meilleur casino français en ligne pour sa ludothèque riche et variée

Arrivé sur le marché des casinos en ligne en 2022, Gxmble a su s’imposer parmi les meilleurs casinos en ligne en un temps record. Voici les quelques points à retenir concernant la plateforme :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Gxmble se hisse d’emblée parmi les casinos les plus sécurisés du secteur en faisant preuve d’une totale transparence en ce qui concerne ses conditions d’utilisation. L’opérateur détient une licence de Curaçao, et bénéficie d’un certificat SSL pour la protection de vos données et transactions.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Gxmble affiche une rubrique assez généraliste sur sa page d’accueil, et vous y trouverez quelques centaines de machines à sous en tout genre, du casino live, des jeux de table comme du poker, du blackjack ou encore du baccarat. Il vous sera aussi possible de réaliser des paris sportifs et Esports. Tous les sports sont disponibles, allant du football au MMA.

💻 Logiciels

Avec plus de 27 fournisseurs de jeux disponibles et représentés sur la collection de Gxmble, vous devriez à coup sûr trouver votre bonheur. Afin de se constituer le meilleur catalogue de jeux possible, Gxmble a fait appel aux plus grands spécialistes du genre dont NetEnt, Play’n GO ou encore Yggdrasil.

💰 Bonus

Dans ce domaine, le casino a fait fort et propose aux nouveaux joueurs un bonus pouvant aller jusqu’à 2500 €, réparti sur vos trois premiers dépôts. D’autres promotions vous attendent sur le site via des bonus de dépôt tout au long de la semaine. Du lundi au samedi, Gxmble offre des boosts sur vos dépôts pouvant aller jusqu’à 1250 €. À noter qu’il vous faudra miser 20 fois vos bonus pour pouvoir retirer vos gains.

📱 Application mobile

Gxmble est clairement taillé pour satisfaire les joueurs de casino qui privilégient majoritairement les smartphones et les tablettes pour assouvir leur passion. Le résultat est remarquable et l’interface s’adapte parfaitement à la taille de votre écran. Gxmble ne soufre d’aucun ralentissement et votre expérience mobile sera très certainement à la hauteur de vos exigences.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

La plateforme propose un large choix de méthodes de paiement dont les cryptomonnaies. Pour s’adapter à l’ensemble de ses utilisateurs, Gxmble met à disposition des moyens comme Neteller, Astropay, Skrill, Giropay, ou encore Sofort. Vous pourrez également régler vos jetons via les cryptomonnaies Bitcoin, ERC20, TRC20, BSC, ou encore Ethereum.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Que ce soit pour les méthodes de paiement traditionnelles ou via cryptomonnaies, vous pourrez déposer un minimum de 25 € pour démarrer votre aventure. Pour retirer vos gains, un retrait minimum de 100 € vous sera demandé, tandis que le maximum mensuel qu’il est possible de retirer est de 10.000 €.

📞 Service client

Si vous êtes face à un problème que vous n’arrivez pas à résoudre, le service client se tient à votre disposition 24h/24 et 7j/7. Vous n’aurez aucune difficulté à contacter un agent, grâce à un chat en direct présent sur la majorité des pages du site. Le délai de réponse est très rapide et les conseillers sont particulièrement compétents et aptes à résoudre vos problèmes. Il est aussi possible de contacter l’équipe par mail.

👍 Avantages

- Plus de 4000 jeux de casino

- Un wager très faible de 20x

- Paiement via les cryptomonnaies

- Un site au design sobre et élégant

👎 Inconvénients

- Pas de mini-jeux

- Pas beaucoup d’informations sur le programme VIP

8. Seven Casino : meilleur casino en ligne fiable qui s’impose déjà parmi les géants du secteur

Nouveau venu dans le milieu des casinos en ligne, Seven est exploité par le groupe GAEM B.V. Pour savoir si ce casino vous convient, voici les informations que vous aurez besoin de connaître avant de vous lancer :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Le casino Seven est totalement sécurisé et détient une licence reconnue de Curaçao. Pour protéger ses utilisateurs le plus possible, Seven Casino a mis en place un protocole de cryptage SSL. Pour garantir une bonne équité des jeux, un logiciel RNG est en place et assure le bon fonctionnement des tirages. Le site Seven Casino affiche aussi clairement toutes les informations légales du site depuis la page d’accueil.

🎲 Jeux de casino

Plus de 3000 titres sont disponibles sur Seven Casino. En quelques clics, il est possible d’accéder aux machines à sous, aux jeux de table, au casino live, ou encore à de nombreux mini-jeux. J’ai aussi apprécié la présence d’un mode d’entrainement, qui permet aux joueurs débutants de se familiariser avec l’interface.

💻 Logiciels

Les meilleurs fournisseurs de jeux de casino du marché interviennent sur la plateforme, dans le but de vous proposer une expérience de jeu particulièrement qualitative. Parmi les développeurs présents, on retrouve des géants comme Play’n GO, Yggdrasil, Relax Gaming, Evolution Gaming, Quickspin, Wazdan, ou encore Novomatic et Playson.

💰 Bonus

Juste après votre inscription et lors de votre premier dépôt, un bonus de bienvenue vous sera octroyé s’articulant autour de vos quatre premiers dépôts. Dans un premier temps, vous serez crédité automatiquement d’un bonus de 200 % jusqu’à 250 €, avec un wager très avantageux de 10x. Vous aurez également la possibilité de profiter de promotions régulières tout au long de la semaine, comme des bonus de dépôt pouvant aller jusqu’à 200 %.

📱 Application mobile

Aucune application mobile n’a pour l’instant été développée, mais l’opérateur permet aux utilisateurs d’accéder au site du casino via le navigateur de votre smartphone ou tablette. S’adaptant très bien aux petits écrans, Seven Casino promet une expérience unique et fidèle à sa version PC. Les appareils mobiles Android et iOS sont tout à fait compatibles avec le soft.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Pour créditer votre compte joueur, vous aurez uniquement la possibilité de déposer de l’argent via des cryptomonnaies. Voici les différentes cryptomonnaies prises en charge sur le site :

- Bitcoin

- Ethereum

- Litecoin

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Étant donné que Seven Casino ne propose pas d’autres moyens de paiement que les cryptomonnaies, un montant minimum de 25 € est exigé, et aucun document ne vous sera demandé lors de vos différentes transactions. En revanche, pour retirer ses gains, il est possible de procéder via virement bancaire, Skrill ou Neteller, en plus de la solution cryptomonnaie. Le minimum de retrait est de 100 € par virement bancaire, et de 50 € si vous utilisez les cryptomonnaies ou les portefeuilles électroniques.

📞 Service client

Côté service client, le site est bien en place et met à disposition plusieurs canaux pour pouvoir contacter le support. 24h/24 et 7j/7, il vous sera possible de joindre un conseiller francophone par mail, mais aussi via un chat en direct. Quel que soit le moyen utilisé, vous serez recontacté dans un délai raisonnable de 24 et 48h.

👍 Avantages

- Un catalogue de jeux conséquent de 3000 titres

- Un wager très accessible (10x)

- Un site ergonomique au design élégant

👎 Inconvénient

- Paiement en cryptomonnaies uniquement

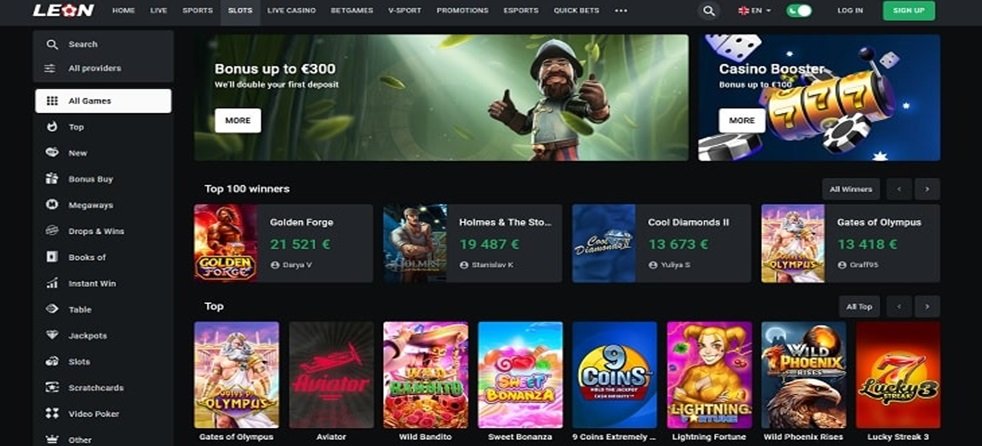

9. Leon : l’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne proposant des jeux et des paris sportifs

Pour avoir passé plusieurs heures sur le casino Leon, je dois dire qu’il fait partie des casinos les plus diversifiés du secteur en termes de jeux et de paris sportifs. Regardons de plus près les caractéristiques de cette plateforme :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Sur cette plateforme, tout est mis en œuvre pour rassurer l’utilisateur et offrir une expérience client sécurisée à 100 %. D’abord, Leon Casino est titulaire d’une licence de Curaçao eGaming Authority, et intègre un système de cryptage SSL de haute sécurité permettant la protection de vos données personnelles et financières. Pour assurer la fiabilité des tirages de tous les jeux présents sur le site, ce dernier utilise un logiciel générateur de nombres aléatoires (RNG).

🎲 Jeux de casino

Leon Casino dispose d’un catalogue de plus de 3000 jeux de casino, dont plus de 1500 machines à sous. Les amateurs de jeux de table y trouveront leur compte avec le blackjack, la roulette, ou encore le baccarat. Une section dédiée aux paris sportifs est par ailleurs disponible, permettant aux joueurs de miser sur l’ensemble des compétitions sportives majeures avec des cotes avantageuses.

💻 Logiciels

Si le casino Leon est en capacité de proposer des jeux de première qualité, c’est en partie grâce aux 35 développeurs qui officient sur le site. Parmi eux, on retrouve des cadors du secteur comme Yggdrasil, BGaming, Spribe, NetEnt, Playtech, Red Tiger, ou encore iSoftBet et Turbo Games.

💰 Bonus

L’avantage du casino Leon se trouve dans la possibilité de choisir purement et simplement le bonus de son choix, ce qui est très rare pour un casino en ligne. Après votre inscription, vous pourrez choisir :

- 100 % de bonus jusqu’à 75 € + 200 spins gratuits (dépôt entre 10 € et 75 €)

- 125 % de bonus jusqu’à 625 € + 200 spins gratuits (dépôt entre 75 € et 500 €)

- 150 % de bonus jusqu’à 1500 € + 200 spins gratuits (dépôt minimum de 500 €)

Le programme VIP est également bien conçu et offre un cashback jusqu’à 10 %, ainsi que des récompenses pour les joueurs les plus actifs comme des bonus de dépôt ou des spins gratuits.

📱 Application mobile

Le casino Leon se démarque substantiellement de la concurrence en proposant une application mobile, téléchargeable depuis Google Play Store et l’AppStore. L’interface est parfaitement adaptée aux petits écrans et intègre toutes les fonctionnalités déjà présentes sur la version PC. Il est aussi possible de vous connecter via votre navigateur sans avoir à télécharger quoi que ce soit.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Les joueurs voulant déposer de l’argent sur le casino leon auront l’embarras du choix concernant les méthodes de paiement. Voici les solutions que la plateforme propose :

- Les virements bancaires

- Les cartes de crédit : Visa, Mastercard, Maestro

- Les portefeuilles électroniques : MiFinity, Skrill, Paypal, Neteller, NeoSurf

- Les cryptomonnaies : Bitcoin, Litecoin, Thether, Ethereum

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Pour déposer de l’argent sur votre compte casino, il vous faudra respecter le dépôt minimum de 10 €. Pour les retraits, vous aurez le choix de la devise, et après avoir vérifié votre compte, vous pourrez retirer un minimum de 20 € qui vous seront restitués sous 2 à 3 jours.

📞 Service client

Avec des conseillers compétents et réactifs, le support du casino Leon se tient à votre disposition par mail ou chat en direct pour résoudre vos problématiques. J’ai été agréablement surpris d’être mis en relation avec un agent francophone qui a très vite ciblé ma demande. Une FAQ est aussi à disposition des utilisateurs sur la page d’accueil.

👍 Avantages

- La possibilité de choisir parmi trois bonus de bienvenue

- De nombreuses solutions de paiement, dont la cryptomonnaie

- Un wager raisonnable (x30)

👎 Inconvénient

- Pas de ligne téléphonique pour joindre le support

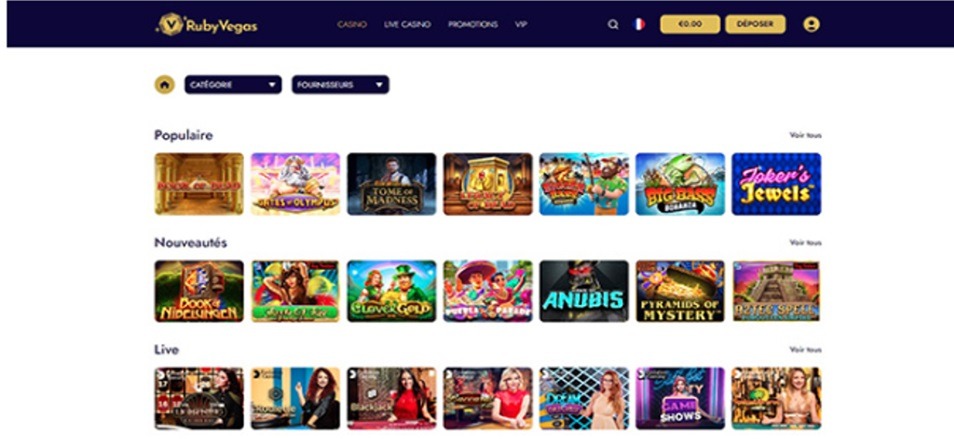

10. Ruby Vegas : meilleur casino français en ligne avec de nombreuses méthodes de paiement

Le casino Ruby Vegas a été déployé il y a peu de temps par la société Mounthberg B.V, qui ambitionne de proposer une offre de jeu de haut niveau aux amateurs de jeux d’argent en ligne. Voici une revue détaillée afin d’en savoir plus sur la plateforme :

📃 Licence et sécurité

Le casino Ruby Vegas veille à la sécurité de ses joueurs et tient à les rassurer en détenant une licence reconnue et clairement mentionnée sur le site. Le site a investi des sommes importantes afin d’implémenter les meilleurs logiciels de cryptage et de sécurité. Ces programmes sont mis à jour de manière continue et sont ainsi très performants.

🎲 Jeux de casino

La ludothèque que propose Ruby Vegas est vraiment conséquente et intègre plus de 4000 titres. On retrouve les mini-jeux les plus populaires, des machines à sous, des jackpots, mais aussi du casino live proposant la célèbre Lightning Roulette et le Dream Catcher. Tous les jeux sont logiquement classés sur la plateforme et accessibles en un rien de temps. Des shows télévisés sont aussi disponibles, et sont animés en direct par de véritables présentateurs.

💻 Logiciels

Pour proposer des titres originaux et à la pointe de l’actualité, le casino collabore avec plus de 40 fournisseurs reconnus dans le monde du gaming. Parmi eux, on retrouve Betsoft Gaming, Evolution Gaming, Evoplay, Netent, Play’n GO, Playson, Pragmatic, ou encore Relax Gaming et iSoftBet. Tous ces éditeurs travaillent autour d’univers ou types de jeux différents.

💰 Bonus

Pour les nouveaux adhérents du casino, un bonus de bienvenue à hauteur de 2000 € est offert, et est échelonné sur les trois premiers dépôts de la manière suivante :

- Premier dépôt : Bonus de 100 % jusqu’à 500 € + 100 spins gratuits

- Deuxième dépôt : Bonus de 100 % jusqu’à 500 € + 100 spins gratuits

- Troisième dépôt : Bonus de 100 % jusqu’à 1000 €

En plus de ça, le casino Ruby Vegas propose des offres promotionnelles régulières comme les Drops & Win, permettant de remporter plus de 500 prix différents, ou encore des bonus sur la machine à sous de la semaine.

📱 Application mobile

L’un des principes du casino est d’être le plus facilement accessible pour tous ses joueurs. En conséquence, Ruby Vegas permet aux utilisateurs d’accéder aisément au site depuis un navigateur, grâce à une simple connexion internet. La technologie HTML5 permet de naviguer de façon très fluide et ergonomique à travers les différents appareils mobiles. Toutes les fonctionnalités et bonus sont accessibles, et les onglets et visuels s’adaptent très bien à la taille des écrans.

💳 Méthodes de paiement

Sur le casino Ruby Vegas, déposer de l’argent sur un compte joueur n’a jamais été aussi simple. De manière sécurisée et rapide, vous aurez la possibilité de réaliser un premier dépôt via cartes bancaires, Skrill, Sofort, Jeton, Muchbetter, Cashlib, Paysafecard, ou encore par virements bancaires et Cash to Code.

💸 Dépôt et retrait minimum

Le dépôt minimum sur Ruby Vegas est de 20 € et ne nécessite pas de délais pour recevoir l’argent. Votre compte casino est crédité instantanément pour vous permettre de vous lancer directement dans l’aventure. Concernant les retraits, les délais sont variables en fonction de la méthode choisie, soit entre 24 et 72h.

📞 Service client

Le service client est d’une utilité cruciale au sein d’un casino en ligne. Les conseillers jouent très bien le rôle de relais entre le casino et les joueurs, et permettent à ces derniers de répondre rapidement à leurs interrogations ou problématiques. Un chat en direct est accessible facilement, tandis qu’une adresse mail est également mise à disposition des utilisateurs.

👍 Avantages

- Un catalogue de plus de 4000 titres

- Un service client compétent et réactif

- Un dépôt minimum de 20 € accessible

- De nombreux moyens de paiement

👎 Inconvénients

- Pas d’application mobile

- Pas de ligne téléphonique pour joindre le service client

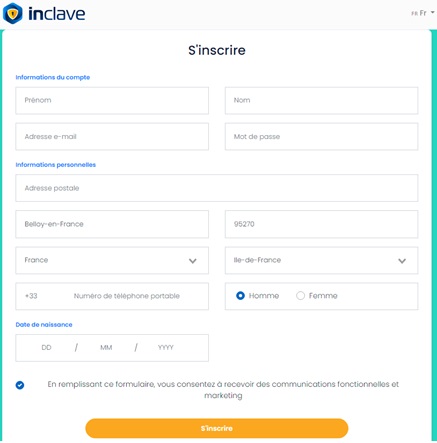

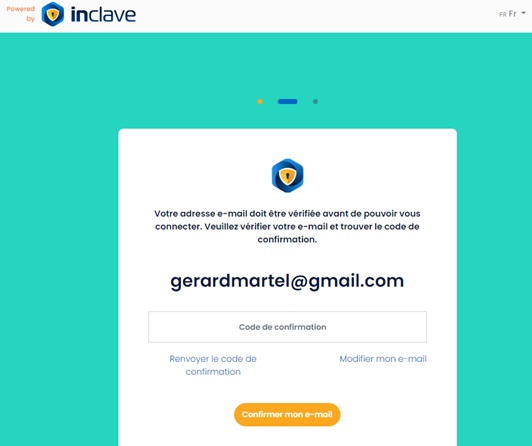

Comment jouer sur un casino en ligne en France ?

Étape 1 : se rendre sur le site Lucky Treasure

Pour vous inscrire, rendez-vous tout d’abord sur le site.

Étape 2 : s’inscrire

Une fois sur le site Lucky Treasure, cliquez sur le bouton “s’inscrire” en haut à droite de la page d’accueil.

Étape 3 : remplir le formulaire d’inscription

Il vous suffit de remplir le formulaire à l’aide de votre nom et prénom, e-mail, date de naissance, ou encore de votre adresse postale.

Étape 4 : validation de l’inscription par mail

Une fois rendu à cette étape, il vous suffit d’aller sur votre boite mail et de valider votre inscription via un lien de confirmation. Après cette étape, vous pourrez commencer à jouer sur Lucky Treasure.

Sur le meilleur site casino en ligne Lucky Treasure, l’inscription est rapide et ne nécessite aucun délai ou téléchargement avant de pouvoir vous lancer dans l’aventure. En parallèle, j’ai apprécié que la vérification des papiers d’identité se fasse uniquement en cas de dépôt, et non au moment de l’inscription sur le site. Je recommande donc vivement de vous initier sur ce meilleur casino en ligne, Lucky Treasure, pour bénéficier d’une expérience inégalée.

Les casinos en ligne en France sont-ils légaux ?

Sur le papier, les jeux comme les machines à sous en ligne ainsi que les jeux de roulette sont interdits sur les sites de casino français. Malgré çela, il n’existe actuellement aucune clause interdisant à un joueur de français de placer des paris dans des casinos en ligne étrangers. À noter que les casinos français permettent tout de même de jouer à des jeux de cercle (blackjack, baccarat).

Du côté des licences françaises, seule l’ANJ (autorité nationale des jeux) est autorisée à délivrer une licence à un casino français qui voudrait exploiter des jeux d’argent en ligne, ainsi que des paris sportifs. L’autorité nationale des jeux est née de la nécessité de mettre en place une régulation des jeux d’argent et de hasard cohérente, dotée de pouvoirs

renforcés afin d’assurer une meilleure protection des joueurs. Ainsi, si vous souhaitez vous inscrire sur un casino en ligne français, veillez bien à ce qu’il soit régulé par l’ANJ, dans le but de vous assurer une fiabilité à 100 %.

Quels sont les bonus casino en ligne disponibles en France?

Dans cette section, je vais vous présenter les différents types de bonus disponibles sur la plupart des meilleurs casinos en ligne de la toile :

💰 Bonus de bienvenue

Lorsque vous avez finalisé votre inscription sur l’un des meilleurs sites de casino en ligne, vous pourrez bénéficier d’un bonus de bienvenue si vous décidez de réaliser un dépôt sur la plateforme. Globalement, les meilleurs casinos en ligne proposent de vous offrir un bonus représentant un certain pourcentage de votre dépôt, jusqu’à 400 %. En plus de ça, vous disposerez selon les sites d’un nombre de spins gratuits.

💰 Casino en ligne bonus sans dépôt

Les casino en ligne bonus sans dépôt permettent aux joueurs de profiter d’entrée de jeu d’un bonus, sans avoir à déposer d’argent sur le site (contrairement au bonus de bienvenue). Je ne vous cache pas que les casinos en ligne qui proposent ce type de bonus sont assez rares.

💰 Bonus hebdomadaire

En vous inscrivant sur l’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne de la toile, vous pourrez débloquer l’accès à des promotions régulières tout au long de la semaine. Spins gratuits, boost de dépôt, jackpots ou encore cashback, la plupart des meilleurs casinos en ligne mettent en place des opérations visant à vous couvrir de récompenses selon votre activité sur le site.

💰 Bonus Cashback

En étant membre du programme VIP d’un casino en ligne, celui-ci vous offrira la possibilité de récupérer une partie de vos pertes chaque semaine ou chaque mois. Pour bénéficier d’un taux de cashback le plus élevé possible, il est impératif de monter les niveaux du programme VIP, afin de prouver votre fidélité au casino et ainsi bénéficier des meilleurs taux de cashback, qui peuvent atteindre jusqu’à 25 %.

Méthodes de paiement

Pour réaliser un dépôt dans de bonnes conditions sur un casino en ligne, les opérateurs mettent à disposition de nombreux moyens de paiement que sont :

- Les cartes bancaires : Visa, Mastercard, Maestro

- Les portefeuilles électroniques : Skrill, Neteller, Ecopayz, Paypal

- Les tickets prépayés : Cashlib, Paysafecard, Neosurf

- Les virements bancaires

- Les cryptomonnaies : Cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin

Toutes ses méthodes de paiement sont fiables et vous permettront d’effectuer un dépôt en toute sécurité depuis le casino en ligne que vous avez choisi.

Dépôt et retrait minimum

En règle générale, les casinos permettront un grand nombre de moyens de paiement pour déposer de l’argent, avec un minimum aux alentours de 5 à 10 € en carte prépayé. Aucun frais n’est à prévoir, et votre argent est crédité instantanément sur votre compte casino.

Pour les retraits, les conditions varient surtout en fonction du moyen de paiement choisie. Le montant peut aller de 1500 € par semaine, à 15.000 € par mois. Un délai relativement court de 24h à 72h peut être appliqué selon les plateformes, le temps pour les équipes du casino de vérifier votre identité et valider votre transaction.

Sécurité des casinos en ligne

En 2024, les meilleurs casinos en ligne pour les français doivent être au minimum détenteur d’une licence reconnue par une autorité des jeux crédible. Les licences les plus reconnues du secteur sont :

- Licence de Curaçao

- Licence de Malte

- Licence de Gibraltar

- Licence de Kahnawake

En dehors de ça, les meilleurs casinos en ligne doivent être en mesure de protéger leurs utilisateurs lors des transactions financières ou lors de la saisie de données personnelles. La plupart des sites de casino sont équipés de logiciels de cryptage SSL de très haut niveau, permettant une sécurité optimale.

Application mobile casino en ligne

Beaucoup des meilleurs casinos en ligne n’ont pas encore développé d’application pour permettre aux joueurs de jouer sur une interface dédiée aux appareils mobiles. Heureusement, et grâce à la technologie HTML5, il est possible de se connecter via votre navigateur pour jouer à vos jeux préférés.

Que ce soit via une application dédiée ou à travers un navigateur, voici un top 3 des meilleures interfaces de jeu via des appareils mobiles :

- Lucky Treasure

- Seven Casino

- Ruby Vegas

Support client

Un bon service client est avant tout l’intermédiaire entre les joueurs et le casino. Pour cette raison, les conseillers doivent être joignables facilement à toute heure du jour et de la nuit. Les meilleurs casinos en ligne proposeront la plupart du temps une adresse mail, et parfois même une ligne téléphonique pour pouvoir contacter un agent rapidement.

En cas d’urgence, il est possible de contacter un conseiller grâce à un chat en direct, accessible depuis n’importe quelle page du casino. Des solutions vous sont en général très vite proposées.

Jeux casino en ligne

Parmi les jeux les plus populaires présents dans les meilleurs casinos français en ligne, bon nombre d’entre eux sont devenus des références dans l’univers des jeux d’argent. Les jeux qui attirent toujours plus de joueurs sur les plateformes sont les machines à sous avec des titres bien connus du grand public comme Hyper Bust ou Juicy fruits. Les jeux de table sont aussi à l’honneur sur les meilleurs casinos en ligne et proposent de la roulette, du baccarat, ou encore le blackjack et le poker.

Des loteries sont aussi régulièrement organisées afin de récompenser les joueurs les plus assidus via des spins gratuits ou des bonus de dépôt. Le casino live est aussi particulièrement à la mode et regroupe des shows télévisés animés par de véritables animateurs comme le Monopoly Live, ou le fameux Deal or no Deal. Des parties de jeux de table avec croupiers sont aussi présentes sur la plupart des sites.

Développeurs de logiciels de jeux de casino

Pour se faire une idée de la qualité du catalogue de jeux sur les meilleurs sites de casino en ligne, il s’agit d’identifier les développeurs en collaboration avec le casino en question. Voici quelques-uns des meilleurs éditeurs du moment à retenir :

- Pragmatic Play

- Evolution Gaming

- Play’n GO

- NetEnt

- Microgaming

- Betsoft

- Yggdrasil Gaming

Comment choisir un casino en ligne fiable en France ?

Choisir un casino en ligne argent réel n’est pas une tâche simple et nécessite une évaluation attentive de la sécurité du casino en ligne en question, méthodes de paiement, des jeux disponibles et bien plus. Voici les principaux critères à surveiller lors du choix d’un site de casino en ligne.

Dépôts et retraits

Dans un premier temps, il est vraiment nécessaire de connaître les modalités de paiement sur le site de casino en ligne que vous choisirez, pour ne pas se faire surprendre une fois votre inscription achevée. Connaître les conditions pour un retrait d’argent est également très important (délais, méthodes de retrait).

🔒 Sécurité

Avant de vous inscrire sur l’un des meilleurs casinos en ligne de notre top 10, vous devez être sûr que la plateforme possède une licence délivrée pas une autorité des jeux reconnue. Ensuite, vérifiez que les dispositifs essentiels de sécurité sont au rendez-vous pour vous assurer d’une fiabilité à 100 % (cryptage SSL, générateur de nombres aléatoires, stockage des données).

💰 Bonus

Portez une attention particulière aux conditions de mise afférentes aux différents bonus proposés. La plupart des sites imposent un wager plus ou moins élevé, qui peut affecter significativement vos possibilités de retrait. Seven Casino propose par exemple un wager très avantageux de 10x, permettant de retirer plus vite ses gains issus des bonus.

💻 Logiciels

L’interface doit être ergonomique et permettre une navigation instinctive. Dans le cas contraire, vous passerez très souvent à côté des offres promotionnelles qui valent le coup et vous pourrez perdre parfois beaucoup de temps pour retrouver vos jeux préférés. Le casino Ruby Vegas, présenté dans notre top 10, est arrivé à allier ergonomie et design agréable.

🎲 Variété de jeux

Assurez-vous que la ludothèque est assez fournie et qu’elle propose suffisamment de types de jeux différents pour vous satisfaire sur le long terme. Par exemple, si vous recherchez une plateforme avec une énorme variété de jeux, le casino en ligne Happy Hugo propose plus de 4500 jeux de casino !

📞 Service client

La qualité du support est un critère que je ne sous-estime jamais. En cas de problème sur le site, qu’il soit d’ordre financier ou fonctionnel, un bon service client saura vous venir en aide dans des délais raisonnables. Il est aussi important de savoir si les conseillers sont francophones afin de se faire comprendre facilement, comme c’est le cas sur le casino Lucky Treasure.

📄 Procédure d’inscription

Assurez-vous que l’inscription se fasse en quelques étapes grand maximum. Globalement, aucun casinotier ne vous demandera de télécharger quoi que ce soit depuis votre ordinateur. Méfiez-vous donc des sites qui vous proposent d’installer des programmes sur votre ordinateur, ou encore des sites qui imposent la saisie de vos données bancaires dès l’inscription.Comment nous avons évalué les meilleurs casinos en ligne en France

Passionné de jeux d’argent depuis plus d’une décennie, j’ai eu la chance d’essayer les meilleurs jeux de casino en ligne et donc de connaître les détails importants à ne pas négliger avant de se lancer dans l’aventure. Étant joueur semi-professionnel depuis de nombreuses années, j’ai choisi de partager ma méthode d’analyse qui vous permettra de vous faire une idée de la fiabilité et qualité d’un casino en ligne.

- Je joue une partie sur tous les types de jeux du site pour prendre connaissance de l’interface et de la jouabilité.

- Je joue plusieurs heures pour être certain de la stabilité du logiciel.

- Après un premier dépôt conséquent pour profiter du bonus, je dépose à nouveau un petit montant et effectue un retrait immédiatement pour être sûr de la fiabilité du site.

- Je m’assure que le site est régulé par une autorité des jeux, si c’est le cas, il n’y a généralement aucune inquiétude à avoir pour jouer sur le site en question.

- Je vérifie que le bonus annoncé est correct et bien respecté

- Je m’adresse au service client afin de connaître le délai de réponse

Casino en ligne avis : Quel est le meilleur casino en ligne fiable français pour 2024 ?

Globalement, les casinos en ligne cités dans notre top 10 font clairement partie des meilleurs casinos en ligne au monde. Cependant, certaines plateformes ne proposent pas encore des paiements en cryptomonnaies, ce qui est un véritable manque à gagner pour la plateforme, mais surtout une possibilité de paiement en moins pour l’utilisateur. Néanmoins, les moyens de paiement déjà en place sur la plupart des plateformes sont généralement très fiables et sécurisés, ce qui rassure l’utilisateur.

Personnellement, j’ai particulièrement aimé passer du temps sur la plateforme Lucky Treasure, qui présente tous les avantages permettant à l’utilisateur de bénéficier d’une excellente expérience client. Lucky Treasure est sécurisé et fiable, avec une ludothèque conséquente, des méthodes de paiement très variées, et un service client au top. Voilà pourquoi je recommande aux joueurs de s’inscrire et d’essayer Lucky Treasure avant tous les autres casinos en ligne de notre top10.

Foire aux questions

Quel est le meilleur casino en ligne en 2024 ?

Il s’agit de choisir le meilleur casino en ligne France qui vous correspond le mieux en termes de jeux et de sécurité. Nous avons défini Lucky Treasure comme étant un des meilleurs casinos en ligne du moment.

Est-il possible de jouer gratuitement sur les meilleurs casinos en ligne français ?

Oui, vous pouvez tout à fait essayer un casino en ligne sans avoir à débourser un euro. Après votre inscription, accédez à la section d’entrainement et jouez sur les jeux dédiés au mode démo.

Comment reconnaître les meilleurs bonus ?

Le pourcentage du bonus doit être le plus élevé possible, avec un wager le plus petit possible (entre 10x et 30x).

Est-il possible de retirer facilement ses gains ?

Dans l’ensemble, les meilleurs casinos en ligne vous restitueront vos gains dans un délai de 24 à 48h selon la méthode choisie.

Les méthodes de paiement sont-elles fiables et sécurisés ?

En effet, c’est une des premières questions à se poser. Assurez-vous que le casino dispose d’une licence valide et reconnue (ANJ, Malta, Curaçao), et qu’il soit en mesure de sécuriser vos transactions en protégeant vos données, via un cryptage de haut niveau.

Avis de non-responsabilité en matière de risques

18 +. Jouez et pariez toujours de manière responsable. Cet article ne constitue pas un conseil de jeu. Les jeux d’argent peuvent créer une dépendance et mener à des problèmes financiers et de l’endettement. Pour obtenir de l’aide, vous pouvez appeler Joueurs Info Service au 09 74 75 13 13.